Listen above or on iTunes / Spotify (Tap the subscribe button – it’s free and keeps you updated!)

Today’s Guest

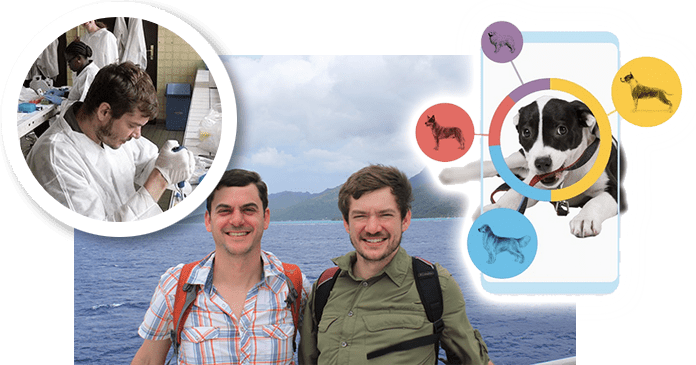

Adam Boyko – Co-founder and Chief Science Officer at Embark – Leaders of DNA Testing for Dogs

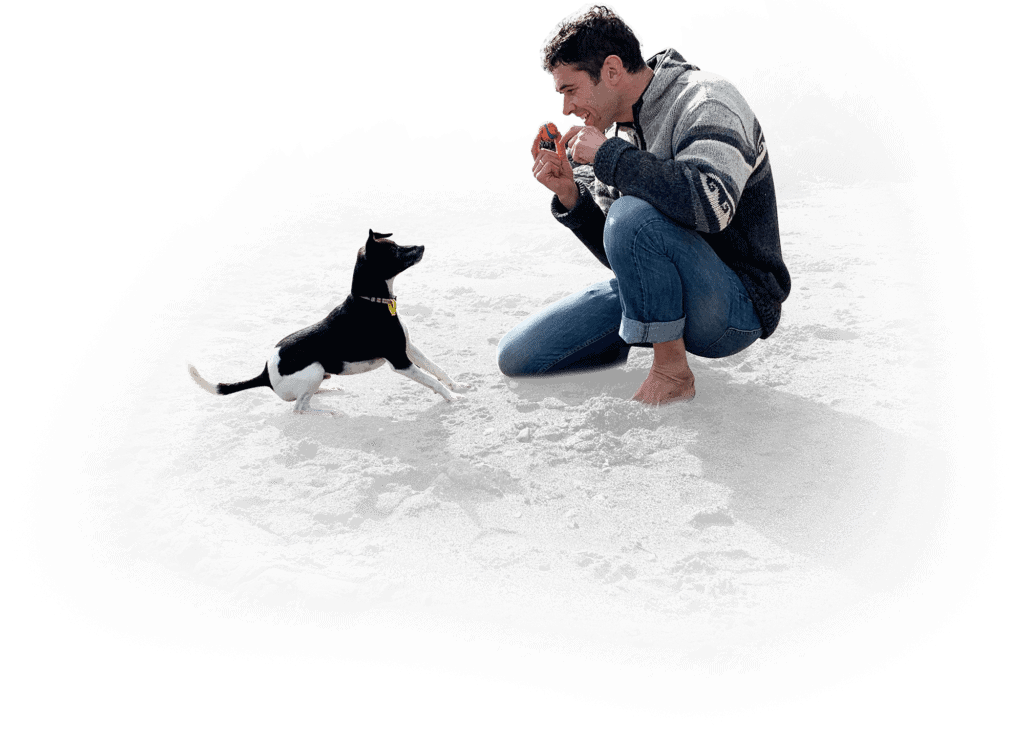

My guest today is Adam Boyko from Embark. Embark is a leading dog DNA testing company, providing dog lovers with detailed analyses of their dogs’ DNA. This process identifies breed makeup and potential genetic health conditions. Embark clients love that their support also contributes to Embark’s ongoing research, done in conjunction with the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Powered by a deep love for dogs and a passion for understanding everything about them, Adam Boyko and his brother, Ryan, have spent the last decade learning everything they could about dogs and asking the deeper question like:

- How did dogs first get humans to fall in love with them?

- How did humans and dogs change each other in the years since then?

- And how can we best care for our furry family members?

Ever wondered what dog DNA testing could tell you about your dog? Tune in to hear this fascinating story of where our dogs came from, and what makes them who they are today!

You’ll Hear About

- [03:45] What Embark is all about

- [08:30] What Embark’s DNA testing can tell you about your dog

- [10:00] The huge number of potential health conditions that Embark can detect

- [10:45] How inbreeding could affect your dog

- [13:45] The first breed of dog genome sequenced

- [14:50] Which breeds are the most inbred

- [16:15] Testing pedigrees

- [17:20] Variations in inheriting DNA … and is Doggy Dan more Egyptian than English?

- [20:37] Intriguing breakthroughs during the Boykos’ research trips

- [22:00] What we know so far about the evolution of wolves into dogs

- [24:00] Purposely bred breeds vs naturally occurring breeds

- [27:00] Is the Dingo a ‘dog’?

- [29:00] How we ended up with such wide and diverse breeds of dogs

- [34:30] The breed of dog that sings!

- [38:30] The rarest and extinct dog breeds

- [40:00] All sorts of interesting things we can identify in dogs’ genomes

- [41:30] The surprising strongest genome signal identified across dog breeds

- [42:40] Who was “Flopsy”?

- [43:15] What you can learn about YOUR DOG when you use Embark’s DNA testing services – and how it can SAVE YOU MONEY!

- [45:30] How a dog’s appearance can actually be misleading when trying to guess their breed

- [46:30] Can breed determine temperament?

- [49:00] How to get a test done for YOUR dog

Special Podcast Only Offer

Adam has extended a special offer to all my podcast listeners. For a limited time you can save up to $50 on a Breed + Health Kit today by using the coupon code they present on their special offer page.

Click the button below and discover your dog’s DNA story…

Save up to $50 on my DNA Breed + Health Kit

Links & Resources

- Embark website: https://embarkvet.com/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/EmbarkVet/

- YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCv5RSkcC9YEY-wQjfdqHfTQ

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/embarkvet

- Instagram: http://www.instagram.com/embarkvet

- If you’re interested in learning more about Embark and Dog DNA Testing, check out this video:

Learn more by tuning into the podcast!

Thanks for listening—and again, don’t forget to subscribe to the show on iTunes / Spotify to get automatic updates.

Cheers,

~Doggy Dan

| Voiceover: | Welcome to the Doggy Dan Podcast Show, helping you unleash the greatness within your dog. |

| Doggy Dan:

[00:00:30] |

Hello, everybody. Doggy Dan here from the Doggy Dan Podcast Show and today I am with Adam Boyko who is the co-founder and the chief science officer of Embark. Now, Embark is the most complete dog DNA testing company on the market. They provide dog owners with information about their pup's breed, your dog's ancestry, your dog's health and more, lots more, loads, loads more which we're going to talk about today, all with just a simple cheek swab. |

| Doggy Dan:

[00:01:00] [00:01:30] |

Adam is an associate professor in biomedical sciences at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, and he's focused on the genomic investigation of dogs. So a fascinating man to have on our podcast show today. Adam's research has addressed fundamental questions of dog evolution and history, disease, trait mapping and advancing genomic tools for canine research. So Adam's co-authored over 40 peer reviewed scientific papers including research in Nature, Science and the Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Science. He's also a graduate of the University of Illinois, Urban Campaign and received an MS in computer science and a PHD in biology from Purdue University before his post-doctoral work at Cornell and Stamford. |

| Doggy Dan: | So as you can see Adam is a highly qualified man that we have on the show. It's an absolute honor to have you here today, Adam. Welcome, and I can't wait to start talking about dogs with you. |

| [00:02:00]

Adam Boyko: |

Thanks so much, Doggy Dan. I'm doing great. Glad to be here. |

| Doggy Dan: | Yeah. So for those of you, for those people listening who are going, "Wow." Like me going, "What does all that really mean?" Can you tell us about what all that really means? I mean I'm just fascinated, how much can you really tell? Tell us about Embark. I know there's three questions there. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:02:30] |

Yeah, indeed. Well, it's a fun time to be a dog geneticist. I mean we got the dog genome in 2005 and it's really just accelerated, everything we've been able to do and the tools we've been able to develop and that was right when I was getting my PHD so- |

| Doggy Dan: | Can I jump in there before I forget to ask you? I don't want to keep doing this though. You say you found the dog genome in 2007? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:03:00] |

In 2005 is when the Boxer genome, Tasha the Boxer, was sequenced and so we've been using the boxer genome and now hundreds and hundreds of additional genomes that have been sequenced since then, to fuel a lot of this investigation and develop tools so that from a simple cheek swab now we can say a lot about a dog. |

| Doggy Dan: | So you're saying that the Boxer genome was effectively found in 2005? Specific to that breed? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:03:30] |

Yeah, so the Human Genome Project finished up a draft sequence in 2001 and then they did a chimp genome project, there was a dog genome project, a cat genome project, a horse genome project. We've gone out now to platypus and armadillo and everything, and everything's got a genome now. But 2005 was sort of the dawn for the dog genome. |

| Doggy Dan: | Got you, wow. Yeah, okay, brilliant. And so carry on, sorry, I interrupted you but I just had to know a little bit more about that genome side of things. So yeah, and so what's Embark involved in and what's the score with all of that? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:04:00] |

So my research into dogs has focused a lot on identifying the mutations that underlie the huge amount of diversity that we see in dogs and also understanding how different populations of dogs relate to each other. Not just pure breeds that we think of, but village dogs that live all over the world and have been living all over the world for thousands of years. And then also trying to answer complicated genetic health questions that owners and breeders are really interested in, things like why are some breeds predisposed to cancer? And, can I predict whether my dog is likely to get allergies or hip dysplasia? Or things like that. |

| [00:04:30]

Adam Boyko: [00:05:00] |

All of those investigations require lots and lots of genetic data. They're not easy questions to answer and particularly for complicated things where there's lots of genes involved, things like cancer, things like longevity, why do some dogs live longer than others. You need samples that include hundreds-of-thousands of dogs that are looked at genome wide, and it was becoming clear in my research at Cornell that there wasn't really a way for an academic lab to do that. There's not the funding from research grants that's going to support that kind of big scale research. I mean it's almost like some of the supercollider research that physicists do, or massive genomic projects that are done in human genetics and are supported by institutions. There just isn't that degree of funding for dogs. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:05:30] [00:06:00] |

At the same time, dog DNA tests when I was starting out were not very scientific and were not based on a lot of data. So in my research lab I could tell a lot more about a dog than what any person buying a commercial dog DNA test would be able to figure out, and so it was this idea, if we could meld the two, if we could use the research grade platforms that researchers use to do dog DNA testing, we can give owners lots more insightful information about their dog. Much more scientifically valid, accurate, comprehensive information and at the same time we can build this database that's going to allow researchers to make the discoveries that we really, really want to make. |

| Adam Boyko: | What's great is we can build that research without using government funding either. So the citizen scientists, the ones that are buying the dog DNA tests, are the ones that are supporting research. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. That's really clever. Yeah, I get it. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:06:30] |

Yeah, well, starting out we didn't know if it would work so it was really nerve wracking. But it's been very fun and the response we've got ... customers have really loved the experience. They love the fact that they're kind of giving back and they're helping make new discoveries with dogs that are going to eventually improve the lives of dogs. So we have high ratings on Amazon and we've built a team of really smart people that are really fun to work with, so it's been very exciting. |

| Doggy Dan:

[00:07:00] |

Cool. So tell us, what exactly would you get back if I was to get one of the tests for my dogs? That's one of the questions I have, I don't know if you can ... Is it possible for me in New Zealand to get one of your test kits? |

| Adam Boyko: | Absolutely. Yeah. |

| Doggy Dan: | Okay. |

| Adam Boyko: | Unfortunately on the website you're going to be paying in American dollars - |

| Doggy Dan: | That's okay. |

| Adam Boyko: | ... and not New Zealand dollars, and the shipping times are going to be a little bit longer, because we process everything in the United States. |

| Doggy Dan: | Anywhere in the world? |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah, anywhere in the world. |

| Doggy Dan: | Got you. |

| Adam Boyko: | The kits are shipped out from the United States. |

| Doggy Dan: | I wasn't sure if I did a dog swab on my dog's mouth, whether it would take too long from my dog to ... |

| Adam Boyko: | No, the swabs are very stable, that's why we use- |

| Doggy Dan: | Yeah, brilliant. |

| [00:07:30]

Adam Boyko: |

... the saliva and it's got a stabilizing fluid in there. The instructions are fairly straightforward and about over 98% of the samples we get back are usable and we can always send you another swab if the first one doesn't take. |

| Doggy Dan: | Well, that'd be fascinating. It'd be fascinating to get you back on this show at a later date when I've got my results back, because I've got some interest in- |

| Adam Boyko: | Sure. |

| Doggy Dan: | I believe, I believe I have a whippet-pit bull mix. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:08:00] |

Oh yeah? So that's been one of the surprises, is all the different pit bull crosses that we've seen. I didn't think that we would come across chihuahua pit bull crosses. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. |

| Adam Boyko: | Or Jack Russel terrier pit bull crosses, yeah, things that you try not to think too much about what went into that dog. |

| Doggy Dan: | Yes. And I have a Catahoula Leopard Dog. |

| Adam Boyko: | Oh nice. |

| Doggy Dan: | Which is mixed with something. So goodness knows how a Texan cattle dog got over to New Zealand, but he's one of the only ones in New Zealand, I know that. |

| Adam Boyko: | Wow. How exciting. Yeah, those are a neat bread, the webbed paws and everything. |

| [00:08:30]

Doggy Dan: |

Yeah, yeah. So what can you actually tell us if I was to do one of these swabs on my dog or you get one in from somebody? In terms of predictions or telling us that it does have cancer or doesn't, and hip dysplasia or how big the dog is? Can you give us an idea? Because for me it's a little bit sci-fi, it's like, "Really? Can you really tell that? And with what degree of certainty?" |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:09:00] |

Yeah, so we go back three generations to look at the mix that's in your dog, and sometimes we can go back a bit farther and detect things that are down to about a 5% influence in your dog's genome. So you'll get the breed mix and a hypothetical family tree with that mix, so you can see whether all the poodle is coming from one parent or- |

| Doggy Dan: | Oh wow. |

| Adam Boyko: | ... there's Poodle on both sides of the family tree or something like that. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow, you can actually tell that? |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah, yeah, absolutely. And we can also tell if there's any relatives of your dog that have tested with us. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. |

| [00:09:30]

Adam Boyko: |

So people get surprised and they're like, "Oh my gosh, I found a brother of my dog halfway across the country." Or in my case, there was a cousin of my dog that I didn't even know existed that's just one town over. So we've gotten to go now and visit my dog's cousin and it's kind of amazing. They've got different fur but it's sort of the same chassis that they're built on and they have many of the same health complications and mannerisms and things like that. So it's really neat to see the genetic influence that way. Most people don't know their dog's family medical history, right? |

| Doggy Dan: | That's hilarious, isn't it? |

| [00:10:00]

Adam Boyko: |

It's kind of a neat thing to look at. But we also test for over 175 different health conditions. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. |

| Adam Boyko: | So mutations that are known to cause blindness or bladder stones, or bleeding disorders, or drug sensitivities, things like that. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:10:30] |

We can test for that as well as tell you how big your dog is expected to be based on it's genetics. We can go through all the different coat color genes that are known, so you can say what your dog's fur should be like, how long it will be, is it going to be curly, is it going to be straight, all those different trait things. And then we also do what I think is neat: the coefficient of inbreeding, right? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:11:00] |

So lots of dogs are inbred, a lot more than humans are inbred, and people don't usually know if that shelter dog that they adopted is inbred or not. Shelter dogs tend to be more outbred than show dogs, purebred dogs, but it definitely ... there's a whole distribution and there's a whole distribution in purebred dogs too. Some of them are still quite outbred, but many of them are very inbred, and we actually see that there are correlations with that. It has an effect, if your dog is more inbred, it's not likely to live as long. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:11:30] |

If you breed the dog it's not going to have as large litter sizes as if it was outbred, and we had a paper published on that, and it's also going to have more health complications while it's alive as well. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. So nature almost shuts that inbreeding down to a certain degree? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:12:00] |

Yeah, so when you're looking at what I call village dog populations or natural dog populations around the world, I mean there's thousands and thousands of dogs in each one of those populations and inbreeding is very low. So genetically they're very … Of course they're in a very stressed out environment, a lot of them aren't getting the food or protection from parasites, predators, things like that. But genetically, they're sort of ... that's how dog populations are supposed to be. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow, yeah. |

| Adam Boyko: | So when we've done selective breeding or if you do back haired crosses or things like that, it can definitely lead to issues and the neat thing is not only can we tell you how inbred your dog is, we can tell a breeder if you were ... how related two dogs are and how inbred the litter would be if they mated those dogs. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. |

| [00:12:30]

Adam Boyko: |

So now they have this tool that they can use to find dogs that are not going to create highly inbred litters, to breed. |

| Doggy Dan: | What do you actually come back with? Did you say it's 67% inbred? Or what does it actually mean? How do you give the feedback? What's the measure? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:13:00] |

Yeah, so that's what we do. We say, "Your dog has an inbreeding coefficient of 25%." So that means 25% of its DNA, the chromosome it inherited from the mother is the same as the chromosome it inherited from the father. So if there's any issue with that chromosome, you've got two copies of it and you're going to have that issue. |

| Doggy Dan: | Got you. |

| Adam Boyko: | Right, so normally you just need one working copy of a gene and you're fine. The problem with inbreeding is if the inbreeding happens to be over a gene that's broken, now because of the inbreeding, you've got two copies of that broken gene, and now your dog is going to have an issue. |

| Doggy Dan: | Ah, got you. |

| [00:13:30]

Adam Boyko: |

So 25% inbreeding coefficient- |

| Doggy Dan: | Is way too high. |

| Adam Boyko: | ... that's the same as if you were to breed siblings together, the litter would be 25% inbred. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. And some dogs- |

| Adam Boyko: | That's actually not very uncommon for purebred dog breeds. |

| Doggy Dan: | Whoa. |

| Adam Boyko: | So Tasha, Tasha the Boxer, the first dog that got its genome sequenced, was 61% inbred. |

| Doggy Dan: | Oh gosh. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:14:00] |

Right? So they deliberately picked an inbred dog to do the genome because I don't know if you know anything about genome sequencing, it's not like reading a book where you start at the first page and you read all the way through. It's like taking a book, ripping it apart, copying it a whole bunch of times and then trying to glue it back together. |

| Doggy Dan: | Got you, okay. |

| Adam Boyko: | And so it's a lot easier to do that if you have an inbred dog because you've only got one set of chromosomes you're trying to glue together instead of two. |

| Doggy Dan: | So when you say 61% coefficient for that boxer dog, that's pretty incestuous in terms of incestuous being a word we- |

| [00:14:30]

Adam Boyko: |

Right. I mean boxers in general tend to have higher than average inbreeding coefficients, so the whole breed is probably around 40%. |

| Doggy Dan: | Whoa. |

| Adam Boyko: | And then of course in some lines there's been relative crossing line breeding that's elevated it even further. |

| Doggy Dan: | Yeah. I mean are there other breeds you can name which you found to have very high inbreeding coefficients? |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah, the highest inbreeding coefficients are probably the Norwegian Lundehund's. So that breed almost went to extinction. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. |

| [00:15:00]

Adam Boyko: [00:15:30] |

And so it's just a few individuals that managed to make the lines that they have now and so you get all these sorts of conditions that are related to the inbreeding. So they have multiple extra toes on each paw and they have other kinds of serious disorders, and so there's a lot of interest in trying to, "Can we keep the genes that we want, but bring in healthy genes and try to retain as much of the breed's characteristics as possible while we rescue it?" |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. Wow, wow, wow. I see that, I mean here in New Zealand, I sometimes look at some of the breeds and because we're a small island with a much smaller number of dogs here, as you can imagine. |

| Adam Boyko: | Right. |

| Doggy Dan: | Country of 4,000,000 people so- |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:16:00] |

Yeah, I mean we even see Golden Retrievers, it's a very, very popular breed but they were founded in the UK, in Scotland and so the US only has a portion of the diversity in the breed and you can see that US Golden Retrievers tend to have slightly higher cancer rates and tend to have slightly shorter lifespans. It's just a difference of the genetic diversity that's there. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. So very, very interesting, I could chat about that all day. Fascinating. When you do get people saying, "Can you test for the purity of my breed?" As in, "Is my dog 100% Rottweiler?" Do you ever get people? Can you do that sort of a test? |

| [00:16:30]

Adam Boyko: |

Yeah. So we do have people that are really interested in that, and the thing is we don't do breed purity tests. That's what registration organizations are doing. |

| Doggy Dan: | Got you. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:17:00] |

We could check a pedigree, we can confirm if you give us the parents or grandparents that those are actually the grandparents or parents of the dog. But a pedigree can go back, I mean for these breed clubs, the pedigree goes all the way back to the founding of the breed, and so the only way you're going to know are all of the ancestors of this dog from that founding breed, is to go into the pedigree. Because DNA, while we can go back easily three generations and sometimes four, maybe even five in some cases, as you're going further back each ancestor on average is only contributing half as much DNA as the next generation. Right? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:17:30] |

You get half of your DNA from each parent, you get about a quarter of your DNA from each grandparent, you get about an eighth of your DNA from each great grandparent. But the thing is there's a lot of variation. So some great grandparents are going to be contributing 20% and some are going to be contributing 4%. |

| Doggy Dan: | Oh, is that right? |

| Adam Boyko: | And so as you get back six or seven levels, now you're to the case where some of those ancestors actually don't wind up contributing any DNA to you. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. |

| Adam Boyko: | Because of the way that the chromosomes get inherited and transmitted through the generations. It's just sort of like playing the lottery. |

| Doggy Dan: | That's fascinating. |

| [00:18:00]

Adam Boyko: |

And if you're back 10 generations, actually you didn't get DNA from most of your ancestors, only a minority of them actually contributed to your DNA. |

| Doggy Dan: | And is that the same with humans? |

| Adam Boyko: | It is the same with humans, yeah. It's actually even worse. |

| Doggy Dan: | So you're saying that some of my ancestors didn't really contribute much? |

| Adam Boyko: | Didn't give you any DNA, right? So one of my brothers, I'm 53% related to, my other brother I'm 47% related to. |

| Doggy Dan: | Whoa, that's so funny. |

| Adam Boyko: | Right? And it just depends on whether we inherited the same chromosomes from mom and dad or not. |

| [00:18:30]

Doggy Dan: |

Oh my gosh. I'm learning way more than I thought. |

| Adam Boyko: | And it's worse in humans than it is in dogs, because dogs have 39 pairs of chromosomes and humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes. |

| Doggy Dan: | I'm learning so much more today, Adam. |

| Adam Boyko: | You're not even flipping the coin as many times in humans. |

| Doggy Dan: | I tell you why I'm chuckling to myself, it's because I have an Egyptian grandfather and I've always said I'm quarter Egyptian. But I think I'm more like 60% Egyptian. |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah, right. No, definitely. |

| [00:19:00]

Doggy Dan: [00:19:30] |

I have this real passion and love of life and I was watching an Egyptian or Arabic food show, no, it was Cairo. It was food stalls in Cairo and I could just associate with all these men who were just getting so excited about the food and hugging each other and it was like my wife was laughing. She's going, "That's you, that's you." So now it explains it. Yeah, I so liked my grandfather so much - that's so funny what I'm learning today.

All righty. So basically, let me just get this right. If people just want to get a DNA test or they want to know how much of their Pekingese, if their dog is 80 or 100% Pekingese, are you saying that your tests are probably not the right ones for them? Is that what you're saying, Adam? I just want to clarify that. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:20:00] |

Well, no. If they want to know if their dog is 80% Pekingese or 100% Pekingese, then absolutely, they should do a DNA test like Embark. But just realize a DNA test isn't going to tell you whether your dog is 99% Pekingese versus 100% Pekingese. |

| Doggy Dan: | Okay. It can't go down to that level. |

| Adam Boyko: | Once you get below 5% resolution- |

| Doggy Dan: | Got it. |

| Adam Boyko: | ... there's not that certainty. If you want certainty, get a pedigree registered dog. |

| Doggy Dan: | Oh, I see. Get one from them, because they'll have done all that. Got it. Lovely. |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wonderful. |

| Adam Boyko: | But if you're okay with a 99% Pekingese then by all means. |

| Doggy Dan:

[00:20:30] |

Yeah, yeah. So I was reading through your website, Adam, you've traveled the globe studying dog diseases and traits and I was wondering, are there any sort of breakthroughs or stories that stand out whilst you were abroad that come to mind that you could share with us? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:21:00] [00:21:30] |

Yeah. Of course traveling is always a lot of fun. Nearly all of this research I actually did with my brother, Ryan Boyko. So he was a grad student at UC Davis in Yale, doing some of his own research but then we were also doing research together on village dogs. So lots of fun times traveling with him and I think one of the biggest breakthroughs we had was sampling dogs in Nepal and having collaborators sampling dogs in Mongolia and I had a postdoc in my lab, Jess Hayward, that did a bunch of the sampling too. Getting back to the lab and analyzing those samples along with all the other samples that we had collected around the globe and seeing this clear pattern of high ... of an increase in genetic diversity that you would normally see associated with the origin of a species, right? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:22:00] |

So where a species originates will have more genetic diversity than where the species spreads out to after it originates. In humans, if you look at the most diverse human populations, they're in Africa, right? And then as we migrated out of Africa, only a subset of the diversity migrated out. Well, with dogs people had been trying to figure out where dogs came from and there were some nice studies with wolves. There were dogs, you compare dog DNA and wolf DNA, but a lot of these studies were just looking at ... either not looking at the whole genome or they were looking at purebred dogs, right? Because that's what most geneticists had in their freezer. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:22:30] |

The problem with doing that is it's kind of like trying to understand human origins by looking at European royal families. You're missing out on a lot of the diversity picture. And so that sort of Ah-Ha moment when you come back into the lab and you're looking and everything is saying, "Wow. We actually have finally found the diversity signature. It's clear that dogs came from somewhere in Central Asia." Which wasn't a place that people had been thinking about before. There's not really a lot of fossil records coming from there. Most of the fossils are in the arctic or in Europe, or in ... there's some in the Americas now that have been analyzed and we've been able to get DNA from. So that was really exciting, we could actually detect this sort of thing. |

| [00:23:00]

Doggy Dan: |

So are you saying that you're pretty sure that that's where the dogs kind of originated from? If that's the right word. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:23:30] |

Yeah, yeah. I mean a lot more research is going to be needed to pin down with more precision. It's a big area, Central Asia, as well as to pin down the timings. Was it 15,000 years ago? Was it 30,000 years ago? I mean the story right now looks like the wolf population that led to dogs split off from the rest of the wolves that we see today around 30,000 years ago. But we don't see anything that's a dog in the fossil record until closer to 15,000 years ago. So maybe they split off, but they were kind of wolves for a long period of time before they evolved into dogs, or maybe we just have a spotty fossil record and we actually had dogs for longer than that and we'll discover that some day. |

| Doggy Dan:

[00:24:00] |

Wow, fascinating. So something I would love to chat about is, and you'll have to help me here, but it feels like there are different ... Let me get this right. Some dog breeds are more sort of man made, developed, through breeding and inbreeding and you know what I mean? For example, the boxer dog seems to be a good example of that. |

| Adam Boyko: | Right. |

| Doggy Dan:

[00:24:30] |

Don't get me wrong, guys. I love boxer dogs. Love my jumping boxer dogs, and yet there do seem to be other dogs which are more ... they've developed naturally due to the location that they've grown up in, such as the Eskimo Dog or the Pharaoh Hound. Can you touch on that? I mean it's not my area of expertise, so I'm struggling to get the right words here, but you know what I'm saying? |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah. |

| Doggy Dan: | Is that actually too specific? Kind of these ones were man made and these ones are natural because it fascinates me. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:25:00] |

Right. So there's clearly a continuum of what I would call dog populations. So I reserve the word ‘breed’ for a more specific type of population, and so the first wolves that were the progenitors for dogs, clearly wolves are wild animals living in wild populations. You had an off-shoot of wolves that suddenly liked hanging around people, right? |

| Doggy Dan: | Yeah. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:25:30] [00:26:00] |

It became better for them to scavenge from human hunting villages than it did ... than it was for them to do their own hunting. In order to scavenge well, you need to evolve a tameness so that you can tolerate the presence of people. Wolves don't typically like people around. You need to also be able to take social cues from the people, be able to intuit whether this person is a danger to you or whether this person is somebody who's going to provision you and is friendly. And then other things can be helpful like a smaller body size so you're less intimidating, so you don't need as many calories, and now you're kind of dining alongside the people so you don't need to train your offspring how to hunt, you can have ... You don't have to have seasonal litters anymore, you can actually breed more than once a year and you can very quickly generate more and more dogs and you can make more and more wolves. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:26:30] |

So now we're to the point where there's 1,000,000 wolves in the world and there's 1,000,000,000 dogs in the world, right? So it was a really successful strategy, but those first dogs, I mean they are village dogs which are still the majority of dogs in the world today. The breeding is not controlled by people at all, even though they're living in an environment that is human dominated. I would call them natural populations of dogs. The number of dogs that are going to be in that population depends on how much free food there is around, and that's what’s going to control the numbers, not people controlling the breeding. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:27:00] |

A very small subset of them have gone back to being truly feral, so things like dingoes that don't require being in a human dominated environment, they can actually survive on their own. If you go to the middle of a random rainforest you're not going to see dogs unless there's people. |

| Doggy Dan: | So the dingo, for example, is that still classed a dog, a dog breed, as a pure dog breed? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:27:30] |

Yeah, it is absolutely a dog, so it's related to other dogs, it went through the same domestication event that all other dogs went through. But then it, when it arrived to Australia nearly 5,000 years ago, it spread out and the environment in Australia was such that they could survive without human help and so they did. |

| Doggy Dan: | It's effectively a dog who just went wild? |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah, absolutely. |

| Doggy Dan: | I love it. Oh, I feel like I need to ask for forgiveness from the dingoes, I've always thought that- |

| Adam Boyko: | Right, so we wouldn't call it a breed because we're not breeding them. |

| Doggy Dan: | Got you, but it's still a dog. |

| Adam Boyko: | It's a population. |

| Doggy Dan:

[00:28:00] |

That's so funny. I really feel quite bad, I don't know why, but I've always thought that it wasn't a dog. I thought the dingo was a different species. |

| Adam Boyko: | Well, no, it was debated. I mean before we had genetics we didn't know. Before we had genetics we weren't even sure that dogs came from wolves. |

| Doggy Dan: | Yeah, yeah, got you. |

| Adam Boyko: | I mean Charles Darwin thought there was so much diversity in dogs, it has to be a mix of two or more wild ancestors because no wild ancestor has as much diversity as dogs do. |

| Doggy Dan: | Got you. |

| Adam Boyko: | So he thought it would be Jackal and Gray Wolf and other people thought Coyote and something else. |

| [00:28:30]

Doggy Dan: |

I see, yes, yes, yes. And that's where I'm coming from with the dingo, I thought that, yeah. |

| Adam Boyko: | But when we did the genetics, it's clear it's ... I mean because all these can interbreed, right? They're all in the same genus, you can have Coydogs, you can have Wolfdogs. But clearly it was this Gray Wolf population from 20 to 30,000 years ago that led to dogs today. |

| Doggy Dan:

[00:29:00] |

So tell me, why is there such great diversion? Why do we have chihuahuas and Neapolitan Mastiffs? Why is there such a huge range? Or am I asking ... is that a silly question? I mean I'm just thinking about fish, you have such a diversity of fish. |

| Adam Boyko: | Yes, but with fish the diversity is usually different species of fish. |

| Doggy Dan: | Whereas this is the same species? |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah, and it's not only the same species, but most mammalian species originated millions of years ago, right? |

| Doggy Dan: | Yeah, yeah. |

| Adam Boyko: | And dogs didn't start diversifying until 15,000 years ago. |

| Doggy Dan: | So why? Why? Why do we have such diversity? |

| [00:29:30]

Adam Boyko: |

It's because dogs were tamed and we could use them, we could breed them for our purposes, right? |

| Doggy Dan: | Ah, yes, got you. Makes sense. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:30:00] |

So cats were domesticated about 10,000 years ago and we do have different cat breeds, but you don't see nearly as ... you don't see Mastiff sized cats, which would be very scary actually, or even chihuahua sized adult cats, right? You don't have that same body size diversity, you don't have the same kind of working diversity for retrieving versus ... It is because we've lived around cats for almost as long as we've lived around dogs, but cats' utility is in the fact that they can reduce the rodent population, and they're solitary. You can't motivate them to do what you want to do. |

| Doggy Dan: | That's for sure. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:30:30] |

But dogs are motivateable and so because of that we've bred dogs to do all sorts of different ... almost anything you can think of, we've bred a dog to do it. |

| Doggy Dan: | So that makes total sense that man's input has had that effect. Yeah. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:31:00] |

Right, right. And people also like dogs that look unique, so when you have a weird mutation that leads to a spotted coat, that gets selected for. If you have a weird mutation that leads to super short legged dogs, then that gets selected for. It's the same mutation that's in Basset Hounds, in Corgis and all these short legged breeds, and Dachshunds, but arose once and people decided they liked and then they just bred it into whatever breeds they wanted to be short. |

| Doggy Dan: | So just going back to my original question, the Pharaoh Hound is ... What is the Pharaoh Hound? The Pharaoh Hound is a dog who just moved into the Arabian area? I mean I want to say Egypt. Being a quarter Egyptian I'm fascinated with the Pharaoh Hound. It's a weird interest to me. |

| [00:31:30]

Adam Boyko: |

Absolutely. Yeah, so one neat thing about dog breeding is that they are very creative and very confusing with their naming. So the Newfoundland Dog was actually ... the breeding stock for that, the foundation stock was coming from Labrador, and the Labrador Retriever came from Newfoundland, right? So the Pharaoh Hound is a hunting dog, but it's the hunting dog of Malta. |

| Doggy Dan: | Malta, yeah, I remember, yeah. |

| [00:32:00]

Adam Boyko: |

So it's not closely related to other Egyptian dogs. |

| Doggy Dan: | No? Got you. |

| Adam Boyko: | It's closely related to other mediterranean dogs, so, like Sicilian dogs and things like that. |

| Doggy Dan: | Would you say that's just a dog that's gone over to Malta, it's been bred a few times, inbreeding, it's developed that breed and it's- |

| Adam Boyko: | Right. |

| Doggy Dan: | What's the word? What's the correct terminology? I don't want to say a man made breed, but- |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah. I mean I call it kind of a traditional breed. |

| Doggy Dan: | A traditional breed. |

| [00:32:30]

Adam Boyko: |

Some people refer to them as indigenous breeds or land races. |

| Doggy Dan: | What'd you say? Land? |

| Adam Boyko: | Land race. |

| Doggy Dan: | Land race. |

| Adam Boyko: | Is another term that's sometimes applied to these. |

| Doggy Dan: | And that's sort of saying that those people in that area, in that land area, developed that breed through inbreeding and it's a traditional breed, yeah, from that area. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:33:00] |

But using traditional breeding methods. So you're breeding a dog to perform a certain function, not to be shown in the show ring. So you don't care too much about the coat color, you just care about whether it can work. You actually don't care too much about it's lineage so you're willing to ... "I really like this dog and crossed it with another dog that- |

| Doggy Dan: | Yeah, functional. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:33:30] |

Yeah. You're just looking for these functional crosses and if it works out, great, and if not you kick those out to the curb and so that's been the process of dog breeding for 10,000 years. I mean we've had sled dogs for 9,000 years, we've had sight hounds for 5,000 years, we've had Moluss or kind of fighting war dogs for thousands of years. I mean it really didn't pick up steam, this pedigreed dog breeding, until the Victorian Era when you started to get hundreds of breeds that were being defined by foundation stock and forming closed populations that you weren't allowed to outcross from. |

| [00:34:00]

Doggy Dan: |

So just trying to separate, for example, you've got your Pharaoh Hound, that does seem to differ though from your dingo, because your dingo is a truly ... it hasn't been bred, it's just- |

| Adam Boyko: | Right. So we're not breeding dingoes at all. Dingoes are a natural population that descended from domestic dogs. |

| Doggy Dan: | And so I put the dingo in the natural population of dogs, sort of natural population. Is that the right word? |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah. And village dogs, so those are going to be natural populations living in a human settled area. |

| [00:34:30]

Doggy Dan: |

And so are there any others like the Dingo? I think that's my real question, because I watched a lovely movie called The Last Dogs Of Winter, you may have heard of it. It's about the Eskimo Dogs and is it they're right up there in the- |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:35:00] |

So not really, I think the closest thing would be a New Guinea Singing Dog, but they are on the verge of extinction. Not a lot is known about them, but they also ... I mean they're actually the cousin to the Dingo. We've fortunately been able to sequence a couple of New Guinea Singing Dog genomes and there is an effort to try to maintain a breeding population of them. |

| Doggy Dan: | The New Guinea Singing Dog? |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah. |

| Doggy Dan: | Does it sing? I'm not trying to be funny. |

| Adam Boyko: | It does. |

| Doggy Dan: | Oh wow. |

| Adam Boyko: | It yodels, it yodels. |

| Doggy Dan: | Oh how beautiful. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:35:30] |

Yeah, so it's kind of neat that some people call these primitive dogs, right? So one thing we think that all dogs do is bark, but actually when you look at the really primitive dogs like Dingoes and New Guinea Singing Dogs, they actually don't have the barking phenotype. So maybe barking didn't arise as early in dogs as we thought it did, or maybe it just happened to get lost in these populations. |

| Doggy Dan: | And so for example the Husky and the Malamute and all that sort of those thicker coated dogs, the Eskimo Dog, they are again, they are these ... What did you call them? The traditional dogs, the land? |

| [00:36:00]

Adam Boyko: [00:36:30] |

That's right. I mean the Siberian Husky today is a pedigreed dog, AKC registered Siberian Huskies but you still see all of those Alaskan Huskies, working dogs up there in Alaska, clearly the progenitors of modern day Siberian Huskies. So you can disentangle a lot of the genetics going on. You can see the traditional breeding practices and there's different types of sled dogs. There's short distance and there's long distance runners and sometimes we mixed in other dog breeds to kind of help for the racing that wasn't there in the original native stock. Lots of interesting stuff going on and really they're magnificent dogs. It's amazing how well adapted they are for this really uniquely challenging athletic performance. |

| Doggy Dan: | Yeah, yeah. Wow. That's just- |

| Adam Boyko: | They burn more calories per day during the race than the bicyclists do in the Tour De France. |

| Doggy Dan: | In a day. |

| [00:37:00]

Adam Boyko: |

In a day. They'll burn 10,000 calories a day. |

| Doggy Dan: | Whoa. |

| Adam Boyko: | You couldn't even feed them enough dog food to make up those calories. You have to feed them raw meat. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. Wow, wow, wow. Yeah, I'd love to go and meet those ... see some sled dogs, just to meet them. |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah, yeah. Because they actually are fascinating in just what they can do. I mean they're born to pull a sled, that's what they want to do. They're not happy unless they're doing it. |

| [00:37:30]

Doggy Dan: |

Yeah, that's the thing. I always love seeing dogs doing stuff that they want to do. I don't like to see dogs which are being made to do stuff they hate. But those dogs just seem to want to run, it's like, stick me on a soccer field, I just love it, I want to play, I want to run. |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah, absolutely. |

| Doggy Dan: | I also love the fact that they seem to have this hierarchy, I may be wrong here, but it feels like I really want to get someone who's a sled dog expert to talk me through this. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:38:00] |

Oh yeah, I'll drop you some names. There are definitely experts that would be able to talk about them much more, in much more detail than me. I have never actually ridden on a sled before. |

| Doggy Dan: | No. The thing which I love is the fact that one of the dogs always wants to be at the front and I look at my two boys, Jack and Moses, and how they fight over who's the leader and who's in charge and it's like, oh my god, I can only imagine when you have 10 dogs all kind of going, “Yeah, he's the leader." |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah, yeah. I just have one dog, unfortunately, but even she ... yeah, it can be issue. |

| [00:38:30]

Doggy Dan: |

Yeah, yeah. Ah, that's beautiful. So I'm just checking the time here. Is there a kind of the rarest dog breed? I mean you mentioned the New Guinea Singing Dog, are there other breeds that you've just found fascinatingly kind of rare or interesting? Or that you have a passion for? |

| Adam Boyko: | Well, I mean some of the most interesting breeds are extinct, so that's about as rare as you can get. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:39:00] |

So the Kuri from New Zealand, which is probably related to the Hawaiian Poi Dog and the Tahitian Dog and all that. We don't really know the genetics of those dogs. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. |

| Adam Boyko: | Right now it would be really interesting to do a study on it. The native Americans had their own dog breeds, many of which have gone extinct, things like the Salish Wool Dog. They actually sheared the dogs each year and made blankets and clothing out of them like sheep because they didn't have sheep. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow, wow. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:39:30] |

And the coats were just amazing for that. Yeah, and I mean in Europe they had different working dog lines that have gone extinct. So they had Turnspit Dogs, some of those short legged dogs actually wound up working in the kitchen to help cook dinner. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow, that's brilliant. Can you think of a time where you've discovered something which blew your mind regarding this dog side of ... the dog DNA? What's the biggest Ah-ha? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:40:00] |

Well, probably the first project with dogs I worked on as a postdoc. I got into a lab and they had really like top notch collaborators working on this project where we were going to look at the genomes of hundreds ... of 80 different dog breeds. Nobody had looked at that many dog breeds before. And I'm coming from this statistical background and one of the neat things you can do with genetic data is you can look across the genome and you can find areas of the genome where you have the signature that, "Wow, there's something going on here." |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:40:30] [00:41:00] |

There's some sort of variant that's getting selected for in some dog lineages and then there's a different variant in that region that's getting selected for in other dog breeds, which is not a pattern that generally happens by random chance. So we looked and, "Oh, okay, well, we see this region and we know." We do the research and we say, "Oh yeah, because it's got short fur versus long fur." Right? Or we look at this and it's, "Oh, these are big dogs versus small dogs." So we had all these different fur measurements, we had all of these different ... We had 50 different skeletal measurements that we were looking at and so we could look at the pattern of variation in the genome and we could look at the pattern of morphological variation and we could figure out what was the cause ... We could find the genes for stuff. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:41:30] |

So I sat down and I looked at all of the places in the genome where we had this signature of ‘there's something going on here’, and we've been able to hook up most of it, but the weird thing was the strongest signal we saw didn't match up to anything we had measured. Went, "What the heck is going on here?" Like what is this most selected region in the dog genome? What's it being selected for? Because it's not related to size, it's not related to shape, it's not related to any of the fur stuff we looked at. As a researcher, what do you do? I've got this list of breeds that are being selected one way, and I've got this list of breeds that are being selected another way, and I finally had to use Google Image Search, and I started going down the list of breeds and very quickly it became apparent. It was ears. |

| Doggy Dan: | What? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:42:00] |

So it was whether the dogs had prick ears like wolves, or whether they had folded or floppy ears like Labradors or Basset Hounds. And so that, because every single breed gets fixed for one kind of ear confirmation and half of all breeds tend to have floppy, folded ears and the other half kind of have the wolf prick ear and that's what it was. We really had to think creatively about the different things that we're selecting for in dogs. You can't assume you know everything because you have a big dataset. |

| Doggy Dan: | That's so funny. Isn't that fascinating? It makes me laugh. |

| Adam Boyko: | Yeah. Science by Google Image Search. |

| [00:42:30]

Doggy Dan: |

Yeah. |

| Adam Boyko: | Thanks a lot, Dan. |

| Doggy Dan: | What was that? |

| Adam Boyko: | I was going to say thanks a lot. I always enjoy going back and telling science stories. |

| Doggy Dan: | Yeah. Well, it also makes me laugh because I've got a dog that I got from the SPCA, she was called Flopsy when we got her, and the reason she was called Flopsy is because one ear was up and one ear was down. |

| Adam Boyko: | That's right, that's right. Yeah, some dogs, they do it that way. Both of my dogs’ ears are folded, but one of them folds more than the other, so she still has that asymmetry going on. |

| [00:43:00]

Doggy Dan: |

Yeah. Well, we renamed our dog Inca because we thought Flopsy was a bit mean. |

| Adam Boyko: | Oh that's nice, it sounds very regal. |

| Doggy Dan: | Both ears go up in a very, very strong wind. If it's above 25 knots, both ears stick up. |

| Adam Boyko: | Nice. |

| Doggy Dan:

[00:43:30] |

Oh, that's just fascinating. So, Adam, if people are interested in getting a test on their dog or what are the main things that they would be kind of using the test for? Just kind of if people are worried about their dog's health or they've got a puppy or they want to know it’s health? What would you say to people? And what are they actually going to get back from you? Just so the people who are interested in finding out more, if you could just give them a run down? |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:44:00] |

Absolutely. I think the genetic health screening is hugely important so that you have some idea whether there is a risk factor. A lot of them, there's things you can do. You can change a dog's environment, you can feed him certain supplements. You can avoid it entirely. Other times, at least you know that that risk factor exists so you know what to look out for, you can save money at the vet clinic because they could do the right test to diagnose it rather than start out with no idea about what's going on. |

| Doggy Dan: | Got you. |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:44:30] |

We've seen countless people write in, thanking us because it saved them tons of money down the road. But even in the absence of the health screen, a lot of people find a lot of utility in just knowing which breeds are in their dog because it helps them think about how their dog interacts with the world and the kinds of things that the dog might enjoy. There were people that had dogs that were half Border Collie and had no idea and had all sorts of behavioral issues and then they put him into herding camp and things like that and they got a whole new lease on life. And there are lots of people who get a lot of fun out of just going through and seeing, "Oh, so that's why my dog's fur looks like this." Or, "That's why my dog's ears look like that." Or, "Oh, there's a cousin of my dog, I can reach out to them." |

| Doggy Dan: | I was going to say, yeah. That's why my dog loves the dog round the corner, because it's his brother. |

| Adam Boyko: | Right. |

| [00:45:00]

Doggy Dan: |

Yeah, yeah. No, I think it's a great point. I mean I often look at myself and I say to people, "Try and guess where I'm from." And they can't, they think I'm maybe Italian or Greek, and as far as I know I've got no Italian, no Greek, but when you mix English with a bit of Egyptian, this is what you get. So you can't tell just by looking at your dog. Your dog may look like a Corgi, but it may have no Corgi in that breed. |

| [00:45:30]

Adam Boyko: [00:46:00] |

Absolutely, absolutely. And yeah, you wouldn't want to just go by a picture to try to figure out what's in the dog. On the flip side, if you get a dog that's mixed up enough it might superficially, yeah, it might superficially resemble a breed that's not in there at all, and some of the breeds that are in that you really can't see by looking at. My brother's dog, I don't know if you've seen pictures of Harley? She was on the kit box for a while, she's on the website. She's clearly this pit bull mix and it turns out she's half American Pit Bull but she's actually a quarter Golden Retriever which you don't see at all because she doesn't have the fur. But she, in many ways, acts like a Golden Retriever. She loves retrieving, she actually carries two Golden Retriever health conditions for vision and ichthyosis. So clearly the DNA are there and it does explain some of her behavior. But if you looked at a picture of her you would never guess and that's 25% ancestry. |

| [00:46:30]

Doggy Dan: |

Wow. Are there any markers to do with dominance of dogs' attitudes? Can you measure anything like this breed tends to have a very assertive manner, or- |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:47:00] |

Yeah. So there are breeds that are more trainable or more dog aggressive or more stranger aggressive. You can measure those axis. The thing is, most of the variation, so unlike things like size or ear type, most of the variation in behavior still exists within a breed. So on average, a Labrador is going to be friendlier than, say, a Poodle. There's a huge range of variation and it's very overlapping. There're many very, very friendly Poodles and there's many Labs that are kind of standoffish. So it's not as clean. |

| Doggy Dan: | No, makes sense. |

| [00:47:30]

Adam Boyko: |

The research into behavioral genetics is a bit harder, it's been slower and that was one of the impetuses of building Embark as well. It's because now we have a huge genetic database of hundreds of thousands of dogs, connected to owners that love to tell us about their dog. So we just ask them the right questions, we can start to get at that because it's really going to have to be addressed with lots of individuals and not just treating breeds as completely different in those ways. |

| [00:48:00]

Doggy Dan: |

Yeah. And as with children, they're born into this world but they're such soft clay, so much of it depends on the training. |

| Adam Boyko: | Absolutely. |

| Doggy Dan: | Doesn't it? The training is- |

| Adam Boyko:

[00:48:30] |

Yeah, it depends on other aspects of the environment. A lot of randomness. I mean if you just happen to be in the womb wrong and became a runt, right? That's not genetic, but it sort of changes everything. But we even see effects of... of course in the womb, the dogs are lined up in a litter, and so a female that happened to be in the womb next to a brother on each side is actually exposed to more male hormones in the womb, right? And so that happens. |

| Doggy Dan: | Wow. |

| Adam Boyko: | It's a completely non genetic factor. |

| Doggy Dan: | Whoa, Adam. I love it. We've covered so much more than I thought we were going to talk about today. |

| Adam Boyko: | It was fun. |

| Doggy Dan: | Huge, huge thank you. |

| Adam Boyko: | No worries. Thanks, Dan. |

| Doggy Dan: | People who want to know more about this, where do they go? What's the best place for them to go to other than all of this ... Well, you go first, I'll tell them about where. |

| [00:49:00]

Adam Boyko: [00:49:30] |

Yeah, yeah. I encourage everyone, I mean if you're thinking of testing or if you just want to learn more, go to EmbarkVet.com. You can see what the tests do but you can also ... we have educational resources there, YouTube videos, blogs, kind of just explaining some of the research we do, some of the interesting facts about dog genetics and how to understand genetic testing. So wherever you want to go, we have stuff for dog breeders, we have stuff for dog owners, we have stuff for students who just want to learn about genetics and they want to learn about it by studying dogs. |

| Doggy Dan:

[00:50:00] |

Brilliant. And of course all of this podcast will go onto the Online Dog Trainer Podcast site, so TheOnlineDogTrainer.com. I'll put a full transcription of this with all the links and pictures and other stuff so you can go there and find out more. And EmbarkVet.com, it is a wonderful website. I've spent ages on it going round and checking stuff out. It's a lot of fun so you can go there. Other than that, guys, yeah, if you've enjoyed this podcast then remember to click on Subscribe... to be alerted when the other podcasts are coming out. So subscribe to us, I'd appreciate that, and other than that, guys, I think we are done. Adam, a huge thank you. It was absolutely awesome. |

| Adam Boyko: | Thank you, Dan. Thanks. |

| Doggy Dan: | And to the rest of you guys out there, have a great day. Love you lots, love your dog and thanks for listening to another episode of The Doggy Dan Podcast Show. |

| [00:50:30]

Voiceover: |

You've been listening to another episode of The Doggy Dan Podcast Show, bringing you one step closer to creating harmony with your dog. |

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.